| By YENI | Friday, May 13, 2011 |

For decades, the Burmese army has been notorious for its horrific aggression against civilians, especially in conflict areas: underage boys have been forced to join the army; young women, mainly in ethnic areas, have been raped and murdered; locals haved been forced to work as porters—and in some cases even used to sweep for landmines.

“For them [the Burmese military], it is just as normal as eating and drinking,” said Myo Myint, 48, a former Burmese soldier who was an eyewitness to such atrocities and is the subject of the film “Burma Soldier,” a powerful documentary about the life of a former Burmese soldier who risked everything to become a pro-democracy activist.

|

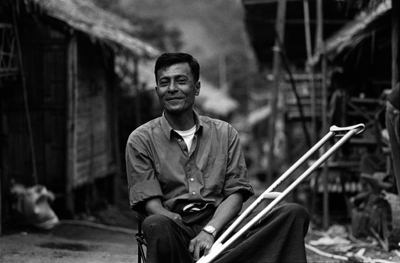

| Myo Myint in Umpiem refugee camp in June 2008 (Photo: Nic Dunlop /Panos Pictures) |

“Burma Soldier” is the first-hand testimony of an ex-soldier who lost his left fingers, right arm and right leg while fighting a skirmish in Burma’s ongoing civil war—one of the world's longest unresolved conflicts which has been raging for more than half a century. The film is a true reflection of a brave, charismatic man who has sacrificed his body and dedicated himself to his country. One of the tragedies revealed by the film is that this Burma soldier is but one of many disabled soldiers who have been neglected by the country's military rulers.

Myo Myint said he joined the army when he was 17 to find safety, respect and gainful employment, later becoming an engineer who mapped and cleared landmines on the battlefield. He soon realized that the soldiers were systematically trained to normalize killing, torture and abuse of civilians in the conflict zones in order to “annihilate the enemies.”

Four years after joining the army, Myo Myint was injured during heavy fighting in northern Shan State. He remained calm, composed and articulate when speaking of battlefield horrors, but began to cry when recalling his mother's visit to the hospital after a mortar had taken off his leg, arm and fingers.

Myo Myint returned to his mother’s home when he left army. There he set up a secret library of forbidden books, reading about history and politics and reflecting on his own life.

The former soldier went on to become an outspoken activist for peace and democracy, and in 1988 he joined student protests and persuaded others to participate in the peaceful demonstrations. Later he was granted a meeting with Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of the country’s founding father Gen Aung San, and became a member of her political organization, the National League for Democracy (NLD). In 1989, he said he believed the opposition party could end the civil war.

Arrested for his involvement in the NLD’s anti-government activity, Myo Myint was sentenced to 15 years in prison. During that time, he was tortured brutally for saying, “ I don’t believe in military regime,” and at one point spent four months in solitary confinement in total darkness.

“My experience in the army was nothing compared with the punishment I received in detention,” he said.

Like other political prisoners, for more than a decade Myo Myint was not allowed to read and write, but often found a way through friendly wardens who sympathized with political prisoners.

He was released at the age of 41, but suffered further harassment by the regime outside of prison. As a result, he decided to leave Burma for the border town of Mae Sot, Thailand, where his prison mates had founded an independent non-profit organization, the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners-Burma (AAPP), which provides assistance to political prisoners and documents news related to them.

“I was introduced to Myo Myint by Bo Kyi at the AAPP in Mae Sot. And I remember Bo Kyi saying, ‘someone should make a film about his life.’ I liked Myo Myint immediately,” said Dunlop, a photographer and author of The Lost Executioner, a book about how he tracked down Khmer Rouge leader Comrade Duch.

Dunlop teamed up with filmmakers Sundberg and Stern, and producer Julie LeBrocquy, to create the documentary. Some narration in the English version was contributed by Colin Farrell, and the archive material included in the film serves as an educational tool for understanding the Burmese army through one soldier's personal story. Of necessity, some of the filming of the army and prisons had to be done using a long lens, but it includes some horrifying footage of Burmese soldiers abusing villagers in ethnic areas and on the battlefields.

The film does, however, have a partly happy ending. The final portion of the film follows Myo Myint to the US, where he was reunited with his brother and sister. He now lives in Fort Wayne, Indiana, which is home to the largest Burmese community in the United States.

But Myo Myint's struggle continues as he joins protests and campaigns in America. Although he accepts the fact that the regime may not fall soon, or even in his lifetime, he believes he has a responsibility to be a voice for the voiceless, serving as a representative for the many foot soldiers in the Burmese army.

In an article last year for the London-based Guardian newspaper, Myo Myint wrote: “I hope it [“Burma Soldier”] will make soldiers serving the regime think about their actions and their treatment of civilians. After watching it, they can ask themselves whether their behavior towards civilians is good or bad, just or unjust.”

Related Article: The Battle’s Not Over (Multimedia)