| By AUNG ZAW | JAN — FEB, 2009 - VOLUME 17 NO.1 |

Washington remains the Burmese people’s best hope for reliable support in their struggle for democracy

AS Barack Obama assumes the heavy duties of the US presidency, the oppressed Burmese people who have seen little political progress in their crisis-racked country are looking to him to see how his Burma policy differs from his predecessor’s.

Although thousands of miles separate Burma and the US, the Burmese people still look to Washington—rather than the capitals of China, India, Russia or any of the EU or

Asean member countries—to provide reliable political support for democratic change.

The question remains, however: will US policy toward Burma under Obama’s administration be low on megaphone diplomacy and heavy on demanding results? More importantly, how will the new administration’s policy differ from the Bush policies that won the appreciation of Burmese inside and outside the borders of Burma?

Obama is no stranger to the Burma issue. When detained democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi celebrated her 63rd birthday last year, Obama—a senator at that time—said the occasion offered “an opportunity to remind the world community of the continuing tragedy in her country and the responsibility we have to press for change there.”

Fine words, but the truth is that Burma’s plight won’t figure among Obama’s top priorities. His attention will be mostly occupied by a worsening domestic economic crisis, while foreign policy concerns like Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, North Korea, Darfur and Zimbabwe will undoubtedly push Burma onto the back burner.

Aung Din, director of the Washington-based US Campaign for Burma, said that although Obama would be “occupied with many pressing issues … we will continue to work with the Congress to remind him of the situation of the people of Burma.”

On the positive side, Aung Din noted: “We still enjoy strong bipartisan support in both the Senate and House. I believe the Congress will help us to put Burma on Obama’s foreign policy priority list sooner or later.”

It’s felt that the Obama team has inherited a lot from the Bush administration stand on Burma, and activists have reason to be hopeful that the Burma issue will attract serious attention.

Burma also commands continuing attention in the US press, and one influential newspaper, The Washington Post, carried several editorials on Burma after Obama won the race for the White House.

“Like South Africans, Burmese will remember who sided with her during their years of oppression and who sided with the oppressor,” the newspaper said. “And as the world watched and measured America’s shifting stance on apartheid, so it will measure the next administration’s commitment to democracy in Burma and beyond.”

In December, former Secretary of State Madeleine K Albright, chairwoman of the National Democratic Institute (NDI), presented the institute’s human rights awards to a staunch supporter of the Burma cause, Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa, and to the Women’s League of Burma.

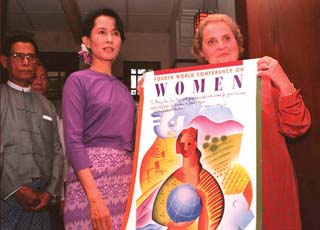

Albright visited Burma in 1995, when she was US ambassador to the UN and met Suu Kyi at the opposition leader’s home in Rangoon, a year after US congressman Bill Richardson had visited Suu Kyi.

Burmese activists recall that it was Bill Clinton who first imposed investment sanctions on the Burmese regime in 1997. He also presented a presidential award to Suu Kyi.

The Burmese have influential friends in the US Congress, and they won’t forget the engagement shown by Bush and first lady Laura Bush during their time in the White House.

Said Aung Din: “Even in the last days of his administration, President Bush and the first lady have put Burma in the international spotlight again and again and set up a precedent for the next administration. We owe them a lot.”

Although preoccupied by his “war on terror” and under heavy criticism at home and abroad for his foreign policies, particularly his invasion of Iraq, Bush nonetheless won the admiration of most Burmese for his firm stance on the repressive regime.

Bush has often been faulted for his tendency to see complex issues in black and white.

But while many condemn him for trying to impose his political perspective on Iraq, few can argue that in the case of Burma, he has taken a genuinely principled stand that is perfectly consistent with reality. Even some anti-Bush critics admitted, albeit uncomfortably, that Bush and his wife Laura were doing something good on Burma.

Bush had a meeting at the White House in 2005 with Shan human rights activist Charm Tong. Laura Bush frequently met Burmese activists in Washington and New York, talked passionately on the subject of Burma whenever she had a chance and strongly pushed the Burma agenda at the White House.

When the regime crushed protests in 2007, she called UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to discuss the situation—a rare approach by a US first lady. She even addressed a challenge to regime leader Snr-Gen Than Shwe to step down. Though no longer the first lady, Laura Bush isn’t quitting, and she’s expected to continue working on the Burma issue.

In 2008, Bush and his wife traveled to Thailand, where Bush met prominent exiled Burmese, and Laura Bush visited the Burmese border, where she met refugees and humanitarian workers. The couple recently met a monk and a blogger from Burma.

Min Zin, a US-based Burmese academic and a contributor to The Irrawaddy, agreed that the Burmese people are indeed fortunate to have the support of both Bush and his wife, who has been a real driving force in keeping Burma at the top of the political agenda.

“It was very much like a personal issue,” he said. The only mistake the Bush administration had made, he said, was to push the Burma issue on to the agenda of the UN Security Council, where a US-initiated resolution was vetoed by China and Russia.

Moves to bring the Burma issue before the Security Council “should be maintained only as a threat,” Min Zin said.

Some Bush critics thought his disastrous Iraq venture had led a number of policy makers in the West working on the Burma issue to oppose US policy on Burma because they were concerned about his foreign policy agenda and growing anti-Americanism.

|

| US President George W Bush signs the renewal of import restrictions on Burma and the Tom Lantos Block Burmese JADE (Junta’s Anti-Democratic Efforts) Act of 2008 in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington in July 2008. (Photo: Reuters) |

Obama’s vice-president, Joseph R Biden, is no stranger to the Burma issue. While chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he played a prominent role in shaping US policy on Burma.

Biden spearheaded the Tom Lantos Block Burmese JADE (the Junta’s Anti-Democratic Efforts) Act 2008, which was signed into law by President Bush on July 29, 2008. The bill renews an act of 2007 restricting the import of gems from Burma and tightening sanctions on mining projects.

Biden said in presenting the bill that it was a “tribute to my dear friend Tom Lantos who worked tirelessly on behalf of human rights for the people of Burma.”

Biden added: “We must continue Tom’s work. Working together with the international community, including the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the EU, India and China, I look forward to the day when a democratic, peaceful Burma will be fully integrated into the community of nations.”

The Tom Lantos Block Burmese JADE Act marks the outline of a strong US policy on Burma. The act has three aims: to impose new financial sanctions and travel restrictions on the leaders of the junta and their associates; to tighten the economic sanctions imposed in 2003 by outlawing the importation of Burmese gems to the US; and to create a new position of special representative and policy coordinator for Burma.

Michael Green, who formerly served on the National Security Council and is currently an associate professor at Georgetown University, was nominated for the post, but the changeover at the White House has put his confirmation on hold.

The proposed US special envoy would have the task of working with Burma’s neighbors and other interested countries, such as those within the EU and Asean. The envoy’s mission would also involve developing a comprehensive approach to the Burma crisis, including pressure, dialogue and support for nongovernmental organizations providing humanitarian relief to the Burmese people.

While Burmese dissidents want Obama to maintain a tough Burma policy, they may want to see some tactical changes and a better strategy.

The prominent Burmese opposition leader Win Tin, in congratulating Obama on his election victory, urged the US to adopt a multilateral approach toward Burma. “We want the US to work with the international community and the United Nations,” he said.

Win Tin, who spent 19 years in a regime prison, warned the US not to compromise with the junta. More effective sanctions and proactive pressure from the international community were necessary for the advancement of the pro-democracy struggle within Burma, he said.

Win Tin appears to have no cause for concern about the steadfastness of US policy on Burma. Ahead of the US presidential campaign, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think tank, said in its October analysis that

Obama would continue to support sanctions against Burma.

The analysis said: “While the dynamics of change ultimately must come from within the country, Obama will work toward achieving a coordinated international approach that includes the nations of Asean, China, India, Japan and European countries to help contribute to the process of reform and reconciliation in Burma.”

Frank Jannuzi, a senior Asia adviser to the Obama campaign, said the Burma question should not prevent a deeper US engagement with Asean. “Rather, the United States should work with Asean to ensure that Burma lives up to its obligation as an Asean member,” he said.

Burma scholar David Steinberg believes the Obama administration won’t change the US sanctions policy without some strong indication of conciliation from the regime. Nevertheless, he expects the new administration “will be more willing to have discussions with the junta.”

There is no doubt that the generals want to forge a normal relationship with the world’s superpower. A decade ago, they even hired lobbying firms in Washington to approach State Department and White House officials in the hopes of improving ties. They abandoned these efforts after failing to make headway with the Clinton and Bush administrations.

When Obama won the election, Burma’s state-run media formally congratulated Obama and Than Shwe sent a congratulatory message.

According to some recent unconfirmed reports, a number of former Burmese ambassadors traveled to Western countries, including the US, on what are thought to have been missions to sound out the incoming administration’s Burma policy. It’s premature to imagine an informal dialogue between the Obama administration and the regime, but such a development can’t be ruled out.

|

| US Ambassador to the United Nations Madeleine K Albright (right) presents a poster commemorating the Fourth World Conference on Women to Aung San Suu Kyi at her residence in Rangoon in September 1995. (Photo: AFP) |

The meeting came at the request of the military junta and was marked by what was described as a frank and free exchange of opinions on both sides. Burmese officials had wanted the meeting to be held in Burma, but US officials declined because they were told they could not talk to Suu Kyi.

Although the substance of the talks between the US and Burmese sides was not disclosed, topics clearly included the continuing detention of Suu Kyi and other political prisoners, US sanctions and the political situation in Burma in general. US officials at the meeting recalled that as soon as they mentioned Suu Kyi’s name the faces of Burmese ministers suddenly changed as if they had seen a ghost.

Further US-Burma talks are not ruled out, although it’s unlikely they would be held in Burma unless access is granted to Suu Kyi.

According to Steinberg: “Unless there are changes, any direct talks would probably take place outside Burma, because it would seem doubtful that an American official would be allowed by the US administration to go to that country and not see Aung San Suu Kyi, which—assuming Gen Than Shwe is still in command—seems unlikely.”

Steinberg did not expect any dramatic changes on Burma under Obama but added: “I think that in many circles in Washington there is an increased realization that the military will be part of the solution or amelioration of Burma’s problems, and that simply asking them to return to the barracks, which was once US policy, is no longer possible or feasible, if it ever were.

“Overall, there seems to be less change and more of the same, to the continued suffering of the Burmese people.”

Min Zin’s concern is whether the new administration’s policy on Burma will focus more on finding consensus than the “do-it-alone” policy adopted by Bush.

The downside of departing from the Bush approach will be more compromise and accommodation with the other international players on the Burma issue, Min Zin said. In this sense, he thought that the goal of achieving a tangible result in Burma would be compromised.

In an interview with the US TV network ABC in December, then US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice—who famously identified Burma as one of the world’s “outposts of tyranny”—said she regretted that the international community had let the Burmese people down.

Her honest confession is welcome—but the Burmese people don’t want to be let down again.