| DECEMBER, 2010 - VOL.18, NO.12 |

PHOTOGRAPHS BY PLATON FOR HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH

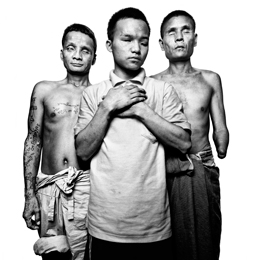

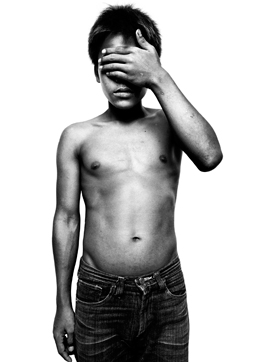

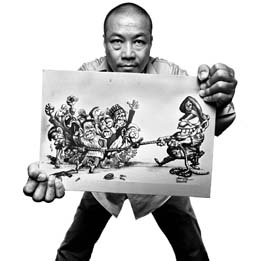

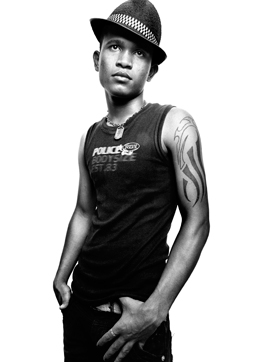

In May 2010, Human Rights Watch took leading portrait photographer Platon to the Thai-Burmese border to photograph former political prisoners, civil society leaders, ethnic minority group members, journalists and other people in exile from their country, Burma.

All of those in this portrait portfolio have experienced human rights abuses in Burma and sought refuge in Thailand. Instead of being demoralized and defeated, they have united and use their shared experiences to educate and work for a better future for all of Burma’s people. Although forced into exile, they have not been silenced.

|

|

In Burma, the HIV/AIDS medication supply is so limited that only one in four people requiring treatment receives it. These children, who are HIV positive, were orphaned or sent by their parents to the Social Action for Women’s safe house, the Children’s Crisis Center in Mae Sot, for treatment or protection. SAW provides shelter, education and basic services for Burmese children including antiretroviral medication.<

|

Shirley Seng, 63, Mary Labang, 36, and Nan Pyung, 21, are members of the Kachin Women’s Association Thailand in Chiang Mai. They speak out against the multiple forms of violence in Burma that result in the displacement, trafficking and migration of indigenous Kachin women, as well as women belonging to other ethnic minorities such as the Karen, Lahu and Shan.

|

|

Burma has the largest number of child soldiers in the world. Here, a 16-year-old former child soldier from Mandalay hides his face to protect his identity. He fled after he was sent to the front line in Kachin state. The overwhelming majority of Burma’s child soldiers are found in the national army, which forcibly recruits children as young as 11, although armed ethnic opposition groups use child soldiers as well. As many as 20 percent of Burma’s active duty soldiers may be children under the age of 18.

|

|

Harn Lay, 44, is Burma’s best-known cartoonist. His work is published in The Irrawaddy. A graduate of the Rangoon School of Fine Arts Academy and former rebel soldier, Harn Lay fled to Thailand following the 1988 protests and ensuing crackdown in Burma. In April 2010, he was awarded a Hellman/Hammett grant, administered by Human Rights Watch.

|

Abu Mayoe and Linda Desube are sex workers from Burma and members of Empower, a Thai organization of sex workers promoting rights, education and opportunities. Most sex workers from Burma provide the main source of income for their families, often supporting five to eight other adults. At Empower in Chiang Mai, migrant Burmese sex workers strive to improve working conditions and promote the dignity of migrants, women and sex workers.

|

The comedic troupe Thee Lay Thee: Mya Sabal Ngone, “Godzilla,” and his wife, Chaw Su Myo. The creative community in Burma has been among the leading voices challenging military rule with art and humor and they are therefore frequently targeted for arrest and detention. The Thee Lay Thee trio fled Burma after their colleague Zaraganar was arrested and sentenced to 59 years in prison in 2008.

|

Kyaw Htet, 22, is a former motorcycle mechanic from Prome. Like many young people in Burma, his opportunities and education are limited, especially if the family has any association with the political opposition. Kyaw Htet left Burma to pursue his dream of being a musician and helping his community.

|

Three exile Buddhist monks (left to right): Ashin Sopaka, Ashin Issariya, known as “King Zero,” and U Teza. In September 2007, hundreds of monks left the relative safety of their monastaries to lead street protests, which came to be known as the “Saffron Revolution.” Burmese government security forces killed, beat, tortured and violently dispersed peaceful protesters, including monks. In the ensuing crackdown, Burmese courts sentenced hundreds of political activists and monks to prison terms of up to 65 years. Many monks subsequently fled the country.

|

Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB) broadcast journalists Thiri Htet San, 30, a former newscaster in Burma, and Moe Myint Zin, 34. The DVB is a satellite radio and television news service, with highly professional reporters who risk their lives to report and record events inside Burma. One DVB video journalist was arrested in 2009 and sentenced to 27 years in prison for filming interviews with monks.