| By LAWI WENG | JULY, 2010 - VOLUME 18 NO.7 |

A Burmese documentary filmmaker highlights the steady environmental degradation of Inle Lake

Burmese filmmaker Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi planned to shoot a documentary about the beauty of Inle Lake, but after seeing the environmental damage the once-pristine lake has incurred in recent years, he decided to use the film to educate the public about the degradation of one of his country’s natural wonders.

|

Inle Lake, Burma’s second largest inland body of water, is located in Taunggyi Township, the capital of Shan State. Encircled by mountains, the lake and its surroundings provide as beautiful a setting as you will find in Burma.

Inle Lake is most famous for its floating houses and gardens and its local fisherman, who stand in their wooden boats, wrap one leg around an oar, and row by swinging their leg wide while dragging the oar through the water.

But as Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi’s documentary shows, the livelihood of these fisherman is now in jeopardy, partly due to the impact of farming practices used in the floating gardens and partly as a result of drought and deforestation in Shan State.

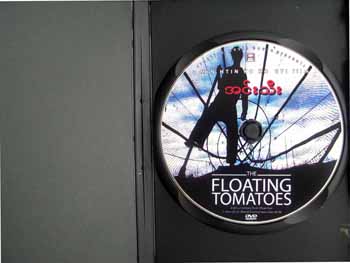

The 30-minute documentary, titled “The Floating Tomatoes,” includes interviews with Inle Lake tomato farmers who have experienced health problems after years of using chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Researched and filmed over a period of one year, it premiered on June 5 at a photo exhibition in Rangoon held by Burmese environmentalists, and will also be shown on the state-run television station, MRTV-4.

More than 100,000 people earn their livelihood by growing tomatoes in Inle Lake’s floating gardens. They use fertilizers and pesticides to produce higher yields, but most are unaware of the negative effect these chemicals have on their health and on the lake. They do know, however, that the water from the lake is no longer safe for drinking and cooking.

“The people use more chemical fertilizers and pesticides than they need, and they don’t use anything to protect their health. They spray a lot of pesticides on their tomato gardens and those pesticides go directly into the water,” Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi told The Irrawaddy.

Chemicals have also greatly reduced the fish population in the lake. This creates a vicious circle, because when people can’t fish for a living, they turn to tomato farming, resulting in even more chemicals being dumped into the lake.

The adverse effects of these practices are not limited to those who live around the lake. The tomatoes are sold as far afield as Mandalay and Rangoon, so the contaminants are “not only dangerous for the people who live on Inle Lake, but also for everyone who eats tomatoes in Burma,” said Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi.

“The documentary is good, but it doesn’t show how we can help the people who live there,” said U Ohn, one of Burma’s most prominent environmentalists, who provided an introduction for the film. “We can’t force the people to stop growing tomatoes because they have no other business. Instead of using fertilizer, we need to educate them about organic cultivation.”

The use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides is not the only cause of Inle Lake’s environmental decline. Both drought and deforestation—which increases the impact of drought by causing silt to build up in the lake—have also played a large role. Burmese environmentalists have found that the climate and biodiversity in the lake have changed to the point that this unique floating world may vanish forever.

“People in Shan State don’t know how to maintain the forest,” said U Ohn. “There is so much logging that it has become deforested. This impacts the people who live on Inle Lake. The water level is getting low and the lake is threatened with extinction in the future. I am worried that the people are going to lose their natural way of life if no one helps them.”

According to a 2007 report by the University of Tokyo’s Integrated Research System for Sustainability Science, Inle Lake has decreased in size by more than one-third in the past 65 years, from 69 square km to just over 46 square km. The report blames the expansion of the lake’s famous floating gardens for 93 percent of the recent loss of water.

While environmentally conscious members of Rangoon’s artistic community did their part to highlight the plight of Inle Lake and its inhabitants, closer to home, others were also trying to raise people’s awareness of the issue.

From June 8 to 13, the Literature and Library Society in Taunggyi held an art and photo exhibition about the impact of climate change on the lake. Titled “Our Lovely World,” the exhibition attracted the attention of people with a keen interest in preserving what’s left of the lake.

One elderly man who attended said: “When I was young, there were 16 marine species that no longer exist today because there is not enough water. The water runs out each year before the summer comes.”

It’s not just the lake, but also its surroundings, that have been hard hit by changes in the climate. As water levels fall, temperatures are rising, reaching as high as 42 degrees Celsius this April, resulting in severe water shortages in many parts of the country, including Inle Lake.

“There used to be a lot of cherry blossoms along the ridge of the mountain,” the old man said. “But nowadays it is so hot in the dry season that most of them have died.”