| By DAVID PAQUETTE | FEBRUARY, 2008 - VOLUME 16 NO.2 |

The first tattoos began accidentally—early man rubbed ash or soot from a fire into cuts and injuries to sterilize a wound. Tattooing became a rite of passage and soon evolved into a magical art

An old Burmese saying goes: “Getting married, building a pagoda and getting a tattoo are the three undertakings that can only be altered afterwards with great difficulty.”

Despite the advice, tattooing has become fashionable again among today’s youth. Even in conservative Burma, pop stars and celebrities are taking up body art and promoting it as cool and chic.

The reactionary Burmese regime doesn’t approve of tattoos, though. According to a Rangoon journalist, the Press Scrutiny and Registration Department has banned images of tattoos in publications. “If somebody—a model or an actor—has a tattoo on their body, we need to erase it on the computer,” he said.

In November 2007, hip-hop star G-Tone was arrested after pulling up his shirt while on stage, revealing a full tattoo on his back. He was subsequently banned from performing for six months.

|

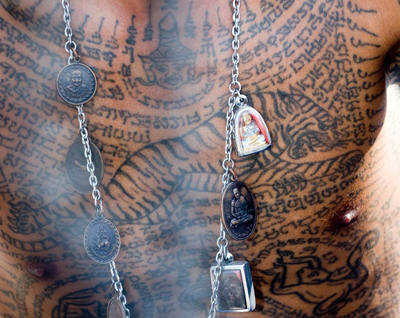

| A young Burmese shows off his body tattoos |

Nowadays, tattoo fans include a wide cross section of Burmese society, from successful sportsmen and pop stars to soldiers and schoolgirls. Whether for cosmetic reasons or religious devotion, for mystical protection from evil spirits or for a simple sense of belonging, today’s youth has taken to tattoo art, piercings and other body decoration like never before.

The word “tattoo” is of Polynesian origin, meaning “to tap,” although almost every culture has developed its own history of tattooing independently. Examples of tattoo cultures and rituals are found all over the world—from the Maori to the Maya, from the Celts to the Egyptians, from the Japanese to the Vikings.

Ancient Chinese records from the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC) indicate that men of the Lue and Yue tribes in the Mekong region were tattooed from waist to ankle with designs of demons and “water serpents”—the legendary naga perhaps—to ward off evil spirits.

However, it was the Shan who popularized the craft of tattooing in Burma, importing the practice from southern China. Their tattoos had magical or spiritual connotations, similar to the belief in amulets.

In Shan culture, a young man was often tattooed from the waist to the knees as a sign of virility and maturity. The ritual was performed by the village medicine man, using a long skewer to apply traditional indigo ink or natural vermillion.

The procedure could take weeks and the subject would be drugged with opium to ease the pain. Common designs were animals, zodiac signs and geometric patterns. Tattooing is still popular among young Shan men, who mostly choose Buddhist motifs.

The introduction of Theravada Buddhism in Burma shaped the symbolism of the art. The body was divided into 12 parts. Hindu gods, Buddhist figures and sacred mantras were tattooed only on the back, the arms and the head. The ears, throat and shoulders were reserved for protective animals and mythological creatures. Tattoos in the pubic area symbolized sexual prowess, using images of geckos and peacocks. A tattoo on the ankles was said to offer protection from snake bites.

Tattoos were not confined to men. Women of the southern Chin clans have tattooed their faces for more than 1,000 years, probably to discourage Burman invaders—a similar custom to the Padaung Karen, who supposedly elongated a girl’s neck with brass rings from an early age to put off would-be kidnappers. For centuries, Burmese women of several nationalities inked subtle “love spots” between their eyes and lips to lure the opposite sex.

Another ancient practice of the Shan and other Burmese was the insertion of silver and gold discs under the skin as a charm against death in battle.

Tattoos also serve that purpose today. Karen soldiers often have a black tiger tattooed on their chests, a custom that is also practiced by some members of the Thai Border Patrol Police.

|

| Tattoos symbolizing protection, using a tiger image and the monkey god Hanuman of Hindu mythology (Photo: Brent T Madison) |

The most common Buddhist artwork is the sak yan, or yantra, the physical expression of a mantra. The image itself is considered sacred and may be a symbol of worship or meditation. Many images, such as the tiger and the lotus, are of Hindu origin. The script of a mantra is in ancient Pali and every line represents a point in the Buddha’s teachings.

Sak yan tattoos are religious, never decorative, and some monks apply the tattoo in invisible ink.

Tattoo Possession

Nowhere can the belief in tattoos be witnessed better than at the annual Wai Kru Festival in late March at Wat Bang Phra in Nakorn Pathom, some 30 km northwest of Bangkok.

|

| Thai men caught up in the frenzy of the annual tattoo festival in Nakorn Pathom near Bangkok (Photo: Brent T Madison) |

The festival itself is spellbinding. Last year at dawn, some 3,000 men gathered in the dusty compound of Wat Bang Phra. Many were of dubious reputation—gangsters, drug dealers and the like—who had been injured in the past and were seeking protection from danger.

Dozens of monks sat at the front of the gathering, quietly chanting. The atmosphere was electric—at one point, the MC on the stage shouted to the crowd: “If you feel yourself going into a trance, please take off your shirt and your amulets!”

Several men had already done so. One or two started shaking uncontrollably. One enormous man with long hair and dressed only in jeans began writhing on the ground. His friends tried to hold him down, but with explosive force he jumped into the air and assumed the stance of Hanuman, one hand outstretched while he held the other above his head as if shaking an invisible tambourine.

The crowd parted to allow him through. With a terrifying shriek he leapt in the air, his eyes rolling back in his head and his body contorted with spasms. Clenching his outstretched fist like a sword, he dashed towards the stage. He careened into a wall of security men. They massaged his earlobes (which is believed to dispel the possessing spirits) and rubbed his back.

|

| A Thai monk tattoos sacred mantras on a man’s head (Photo: Brent T Madison) |

Mass hysteria exploded a short while later. More than 30 men tattooed with images of monkeys, dragons and tigers went into a trance, screaming and writhing, then charging the stage. The security line stayed firm and held the men at bay. The group quietened down and returned to their seats.

At the end of the ceremony, the abbot sprinkled holy water on the faithful who thronged the stage. Then it was the turn of the monks to go to work. Each took his place at a small table, where queues formed to receive a mystic tattoo.

The monks chanted softly as they worked. Concentric lines of yantra were sketched into the backs and shaved skulls of the devotees all day. The men offered incense, fruit, cigarettes and small wads of cash to the monks. Then they left, no doubt feeling that little bit safer if not immortal.